Chronicle 22. AN IBERIAN PERIPLUS REVIVAL

/ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΑ/ Χρονικό 22. ΑΝΑΒΙΩΣΗ ΠΕΡΙΠΛΟΥ ΤΗΣ ΙΒΗΡΙΑΣ

● Tartessos (B) ● Colonies in Provence, Iberia, Maurusia ●

Tin Route ● Democritus and Plato ● Topography Beyond

the Pillars of Heracles

Michales Loukovikas

AFTER THE SEA PEOPLES’ RAIDS and the following Bronze Age collapse in the 12th century BCE, the Phoenicians started setting up their sea-trade monopoly. Carrying out their “master plan”, and enjoying a free hand, as their antagonists were passing through a long “Dark Age”, “they headed straight for the gold, silver, and tin of Iberia”, and became “partners” with the Tartessians. At last, they were masters of the Mediterranean! A lot of Phoenicians chose to settle in local towns, profiting from their hospitality. That’s what Strabo implied writing that “the best cities of Tartessos were inhabited by the Phoenicians”.

Later they secured a harbour of their own nearby. It was Gadir, the “walled city”, called Gádeira by the Hellenes, and Gades by the Romans (modern Cádiz).(1) Its founding is dated traditionally to 1104 BCE, although no archaeological strata there can be dated earlier than the 9th century. Therefore, we assume that in its earliest days, it was merely a small seasonal trading post. According to a Grecian legend, the city was founded by Heracles on Erytheia, Geryon’s island, when he killed him. One of its notable features in antiquity was a temple dedicated to the Phoenician god Melqart, who was associated with Heracles by the Greeks. It was still standing during the 1st century, and some historians believe (based in part on this information) that the columns of this temple were the origin of the myth about the Pillars of Heracles.

Phoenician gold ring with two dolphins, a symbol of Gadir

- (1) Gadir means wall, fort, and this in turn means the walls were the distinctive feature of the city in an area and era when cities were probably not walled. It also implies that the Phoenicians felt the need of such protective walls. Consequently, their relations with the locals were based on anything but in good faith since the beginning.

● The Phoenician settlement was built on one of three neighbouring islets in the Gulf of Cádiz, known as Erytheia, Cotinussa, and Antípolis, which are all Greek toponyms.

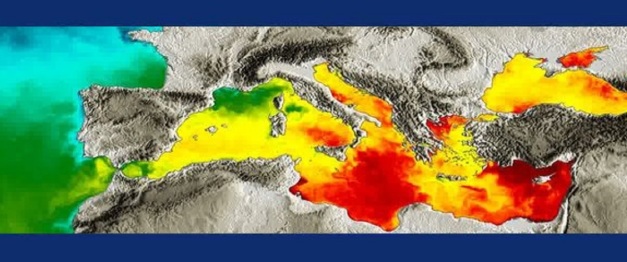

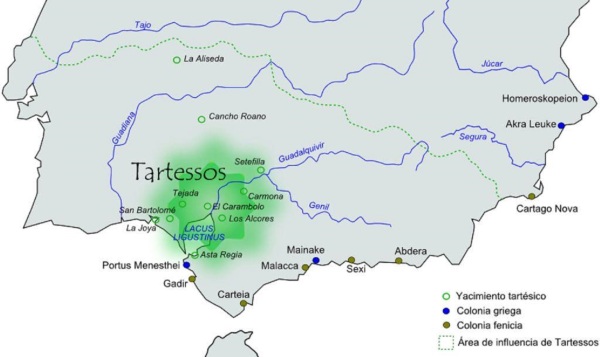

Soon the entire coastline around this strategic area, on both seas and continents – the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, Europe and Africa – was full of Phoenician settlements. However, they were more densely concentrated there, in the south, than further up the coast. So, the Hellenes, when they finally re-appeared on the scene, were able to establish their own trading emporia along the northeastern coast before venturing into the Phoenician zone. Encouraged by the Tartessians, who strongly desired an end to the Phoenician economic monopoly, the Greeks stepped on Andalusian soil and founded Maenaca (Mainakē), very close to the Phoenician Malaca, on the coast of Málaga, possibly at modern Vélez-Málaga. The Massaliote Periplus, which gave an account of a sea voyage round Iberia in the 6th century BCE, placed Maenaca in the dominion and under the aegis of Tartessos: the peninsula was a magnet for everyone due to its great wealth and strategic importance.

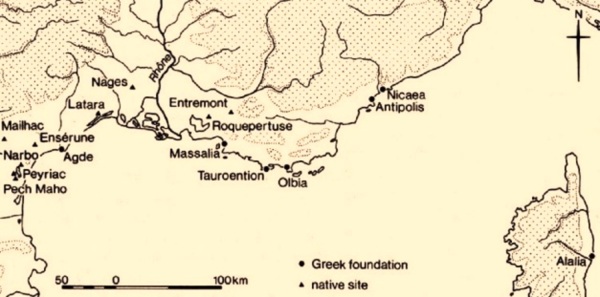

Tartessos, with Phoenician and Greek colonies: its core area is shown in green,

with its sphere of influence spreading in the entire southern Iberia.

Regarding the uncertainty on the whereabouts of Maenaca, Strabo pointed out in his Geographica that its ruins, close to Malaca, could still be seen in his time (64 BCE – 24 CE); he additionally collated the regular Greek urban plan versus the haphazard Semitic layout of the Phoenician site, whose location suggests it was a more dense and irregular urban cluster than neighbouring Maenaca.(2) But even if we are still puzzled about the latter’s exact site and life span, the Hellenic cities on the Mediterranean coast of Iberia probably appeared on the “map” after the foundation of Massalia (modern Marseille), c. 600 BCE, by Phocaeans from Ionia in Asia Minor – something that the Punics had tried but failed to prevent. This city gradually became a thriving trading centre and a major rival of Carthage for the Iberian markets, and especially the tin trade through Gaul-France.

- (b) The father of urban planning was Hippodamus (Ἱππόδαμος, 498-408 BCE) from Miletus, an urban planner, architect, mathematician, physician, meteorologist and philosopher, hence the Hippodamian plan of city layouts. Most impressive in his plan was a wide central area that was kept unsettled and in time evolved to the agora, the centre of both the city and its citizens.

Later on the Phocaeans founded Alalia in Corsica c. 566 BCE and moved towards Iberia. Some popular theories claim that at least one of their settlements, Rhode (modern Roses), at the northeastern tip of Iberia, dates back to the 8th century, as a colony of the Aegean island of Rhodes; but in fact, it seems it was founded in the 6th century BCE by Massaliotes, perhaps with some admixture of colonists from nearby Emporion (today’s Empúries). Still, as in the case of the Phoenician settlement in Gadir, Rhode might have been nothing more than a small seasonal trading post of Rhodes in the 8th century; or perhaps, the colonists that settled there, two centuries later, were mainly Rhodians serving in the Massaliote army, along with Cretans, in a special force charged with surveying vigilantly the Punic movements in southern Iberia.

Nevertheless, popular theories should not be discredited and discarded without serious thought or research, just because they are “popular”; those concerning Rhode, for sure, were not born out of nothing. Sailing towards Provence, we can see that traders from Rhodes were visiting this coast since the 7th century BCE. Rhodian pottery from that century has been found in the area of Marseille, near Istres and Martigues, and at Évenos, near Toulon. The Rhône (Greek Rhodanós), the main river of Provence, and the ancient town of Rhodanousia, were named after the island of Rhodes. There is still a problem of a time gap of one century with the supposed Iberian settlement of Rhode; but, at any rate, the traces left by Rhodians in Provence (and elsewhere) precede those of the Phocaeans, the founders of Massalia.

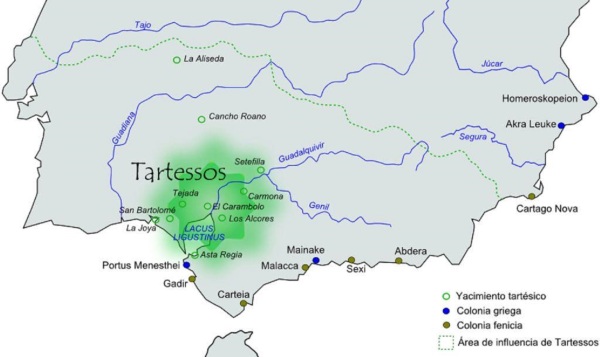

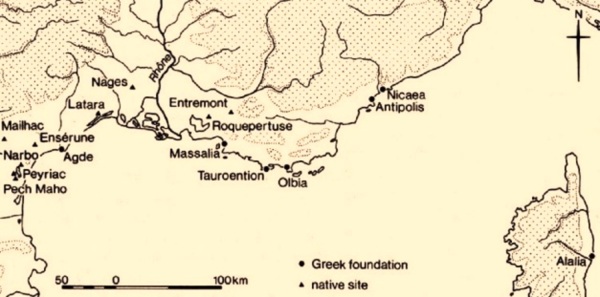

Hellenic colonies in Provence and Corsica

Hellenes from other cities of Ionia also traded in the western Mediterranean, as far as Iberia, but very little remains from that period. As regards the Phocaeans, it is obvious they went there not just to trade, but also to settle. A foundation myth reported by Aristotle in the 4th century BCE, and by Latin authors later on, symbolizes the intermarriage between Hellenes and locals, recounting how a Phocaean, named Protis (or Euxenus), married a local princess, called Gyptis (or Petta), thus giving him the right to receive a piece of land where he could found a city. Contacts developed undisputedly from 600 BCE onwards between Celts, Ligures and Greeks in Massalia and other colonies such as Agde (Agathē Tychē), Nice (Nicaea), Antibes (Antípolis), Monaco (Mónoecos), et al. An Olbia (modern Hyères) was founded here in Provence, and another one in Sardinia.

A Tin Route linked Cornwall to Massalia through the Channel,

the Seine valley, Burgundy and the Rhône-Saône valleys.

The Vix Krater, an imported Greek wine-mixing metal vessel, the largest known from antiquity (1.63 m in height), found in the famous grave of the Celt “Lady of Vix”;

ca 500 BCE

“Massalia was not an isolated Greek city, but had developed an Empire of its own along the coast of southern Gaul by the 4th century”, claimed Charles Ebel in the 1960s. Nevertheless, this idea of a Massaliote Empire is no longer accepted by several skeptical scholars in the light of recent archaeological evidence, which shows that Massalia’s chora (agricultural territory under its direct control) was never large enough. The same skeptics also dispute the idea of a Hellenization of southern France due to Massalia. However, its influence was felt all through Gaul to Brittany, because of the trade relations of the Massaliotes with the Celts, especially for the transport of tin from Brittany, or even Cornwall. It seems that a Tin Route, indispensable for the manufacture of bronze, was established at that time from Cornwall, through the Channel, along the Seine valley, Burgundy and the Rhône-Saône valleys to Massalia. Caesar reported (during his conquest of Gaul) that the Helvetii were in possession of documents in Greek, and all Gaulish coins used the Hellenic script until about 50 BCE. The Massaliote coinage by that time circulated freely in Gaul, influencing coinage as far afield as Britain. Hellenic Marseille eventually became a centre of culture, and that is why several Roman parents sent their children there to be educated.

The Massaliote Periplus Revival

ΟUR MASSALIOTE PERIPLUS REVIVAL SETS SAIL from Massalia’s harbour. Leaving both Rhode and Emporion behind us, we drop anchor between Barcinōn and Callípolis. Legends say that Barcinōn, modern Barcelona, was founded either by Heracles, in the middle of 12th century BCE, or Hamilcar Barca, Hannibal’s father, in the second half of 3rd century BCE. At that time, the Laietani, defined as a Thracian–Iberian people, settled in this area. Some scholars identify Barcinōn with Callípolis, a small Greek colony, which was founded in the 6th century by the Llobregat river. It is described by Avienus in his Ora Maritima (Sea Coast), based on the Massaliote Periplus. But Callípolis should have been at some distance off Barcelona, between Tàrraco (Tarragona) and another Hellenic port, that of Sálauris (Salou), on the Costa Daurada (or Golden Coast) of what is now Catalonia.

The Argonauts’ route according to Apollonius: they never got close to Iberia…

● The legend about Heracles as a founder of Barcelona is unrelated to his colonizing effort in Andalusia following two of his labours there (10th and 11th: Geryon and the Hesperides). His passage from Catalonia is linked to a different version of the myth of the Argonauts, in which Jason’s expedition involved not only the Argo, but nine ships in all. One of them was lost during a storm off the Catalan coast, and Heracles eventually found it wrecked by a small hill, but with the crew saved. These Argonauts were so taken by the beauty of the place that they founded the city of Barca Nona (“Ninth Boat”). Well, it is not only that the city’s name resembles that of Barcelona only in Latin; we also need to remember that Heracles deserted the Argonauts (or… they deserted him) while he was searching for his companion, Hylas, in the outset of the expedition, when the Argo was still in the Sea of Marmara. Others, however, say that Heracles went as far as Colchis with the Argonauts, got the Girdle of the queen of the Amazons, Hippolyta, and slew the Stymphalian Birds (his 9th and 6th labours respectively, organized not in a chronological order). Whatever the case, he could not build Barcelona because he was not among the Argonauts when they fled from Colchis, wandering afterwards in the Mediterranean. But do we know how they fled?

The secret of the Orphic song was not loudness: just one male voice against so many Sirens could never prevail. The secret was its quality, a kind of music they had never listened before,

that drowned out their song and eventually the Sirens themselves.

● There have been several versions of the Argonauts’ expedition – about their route, even crew (see Chronicle 15, footnotes 7 and 8). There is unanimity on the way they voyaged to Colchis; but differences appear about their way back. Pindar (6th–5th centuries BCE), the celebrated lyric poet, sang in his Fourth Pythian Ode that Jason moved eastwards (not westwards) and, through the Phasis and Cyrus (Rioni and Kura) rivers, sailed out to the Caspian Sea. Then, based on the geographic knowledge of the time, he found himself in the Oceanus River encircling the earth, turned south and west, voyaging as far as the Red Sea, and in this way he returned to the Mediterranean. Herodorus of Heraclea (between 6th and 4th centuries BCE) adopted a more realistic approach that the Argonauts used the same route to go back home. The historian Timaeus of Tauromenium (modern Taormina in Sicily, c. 345 – c. 250 BCE), maybe inspired by the great European periplus of his contemporary Pytheas of Massalia (see Chronicle 16, Peripli of the Classical and Hellenistic eras), gave a wider scope to the Argonauts’ nostos. Through the Maeotis (Azov) lake and the Tanais (Don) river, he maintained, Jason found his way up to the Baltic Sea and, sailing by round Europe, he returned home to Iolcus. The Argonautica by Apollonius of Rhodes (3rd century BCE), the only surviving Hellenistic epic, is far more detailed and adventurous, but never sails beyond Italy. Finally, the Argonautica Orphica, written much later (5th–6th centuries CE) but in the name of Orpheus, who was one of the Argonauts, borrows from all the above, emphasizing the role of the Thracian musician, poet, and prophet. The narration is more mythological, probably because of the anonymous author’s everyday life in a hostile Christian environment, after the old gods were violently thrown out (see our additional Chronicles 23-24: The Genocide of the Hellenes, and The Triumph of Cretinism). In the beginning, he adopts the Pindaric version, but as soon as he finds himself on the Caspian waters, he follows in Timaeus’ steps and turns north, not south: the river now is not the Don but the even longer Volga, and the result, of course, is another periplus of Europe.

In memory of the Zácantha citizens who determined to die rather

than fall into Punic hands in 218-19 BCE, by Agustín Querol

BACK TO OUR IBERIAN PERIPLUS. Sailing on while keeping a steady course to the southwest, we arrive at Zácantha or Arse, founded by Greeks from the island of Zácynthus in the 7th century BCE. Captured and destroyed by Hannibal during the 2nd Punic War (219 BCE), after eight months of the citizens’ heroic resistance related by Livy, it was rebuilt by the Romans who transcribed it as Saguntum, hence its current name of Sagunto.

After Valentia (Valencia), our course turns southeast due to a headland jutting out on the coast of Iberia. Sailing past this area formed by Montgó Massif, we stop at the first port marked on the map of Tartessos, Hēmeroskopeion, located at modern Dénia, in the Valencian province of Alicante. It means Watchtower in Hellenic and it reflects the first use of the lofty promontory as such. According to Strabo, the town was also called Artemisium, because there was a temple of Artemis on the cape where it was situated. Hēmeroscopeion was another colony of the Massaliote Greeks, along with two more small settlements in the area, the names of which have not survived. The Romans called it Dianium, whence its modern name, from Diana, i.e. Artemis in Latin. Apart from its strategic location, the city was equally important for some iron mines nearby.

Lady of Elche

Althaea (today’s Altea) was located further down the road, and then Acra Leucá, also built by the Massaliotes on a White Promontory, or Acropolis, as the name indicates, c. 325 BCE. The city passed to the Punics who used it as a military base and trade post. Its Carthaginian name did not survive, but the Romans called it Castrum Album, meaning almost the same. Most archaeologists agree that the Roman town Lucentum, or Lucentia (Luminous city), is Acra Leucá – what is now the modern city of Alicante.

Helice, modern Elche (Elx in Valencian), was founded around 600 BCE near Acra Leucá to the South. The Achaean settlers named it after their native city.(3) Here, too, Hannibal was a fateful man. It was rebuilt by the Romans as Ilici. There was also a small walled coastal settlement, the Roman Portus Ilicitanus, Harbour of Helice, mentioned by Claudius Ptolemy in his Geography; it’s today’s Santa Pola. Built with a regular layout in the Grecian tradition near the Vinalopó river in the 4th century BCE, it served as an emporium oriented to Greek-Iberian exchange. But its life span was brief (c. 80 years), which is inconsistent with the hypothesis that the Massaliote colony Alonís, or Alonae, was there. So, despite Ptolemy’s mention that created more confusion, attention was recently turned to a nearby town, La Vila Joiosa, as a possible location of this colony. The increasing amount of archaeological evidence for Greek presence in Santa Pola, combined with the Graeco-Iberian script used in Alicante and Murcia, confirm the long-term direct contact between Hellenes and Iberians in this area. The celebrated Lady of Elche (Dama de Elche, or Dama d’Elx in Valencian), a once polychrome stone bust of a woman, is the most important find there. It’s considered as an excellent example of Iberian sculpture with strong Hellenic influence. It is claimed (Encyclopaedia of Religion) that the Lady is “directly” linked to the Punic goddess Tanit. If so, then perhaps, in the absence of Phoenician sculptural standards, the Grecian model was unchallenged.

Bronze coin with the patron Poseidon and the inscription ELIK(e), and a trident flanked by

dolphins on the reverse

- (3) Helice (Ἑλίκη) was an ancient Hellenic city in Achaea, in the north of the Peloponnese, which disappeared a winter night in 373 BCE. It was thought to be a legend like Tartessos until 2001, when it was rediscovered in the Helice Delta. The catastrophe is attributed to an earthquake and accompanying tsunami, causing the area to sink into the earth and be covered by the sea. All the inhabitants perished without a trace, despite a search and rescue effort involving 2000 men. The only thing that was left there were a few building tops projecting from the sea. Around 174 CE, Pausanias reported that the walls of the ancient city were still visible under the water. Others said that Roman “tourists” frequently sailed over the site, admiring the city’s statuary! As time passed by, the site silted over and the location sank into oblivion. Modern scholars argue that the submergence of Helice might have inspired Plato to write his story about Atlantis.

Mastia (Massia) > Qart Hadasht > Cartago Nova > Cartagena

The trading contacts of southeastern Iberia with Tartessos, Hellas, Phoenicia and Magna Graecia, together with the absorbed influences, gave rise to an Iberian culture that Pliny and Strabo called the Contestani. Cartagena, originally named Mastia, or Massia, is located here. Mastia (or Massia) was also the name of an Iberian tribe allied with the Tartessian confederacy. The first description of this city with high walls appears in the Massaliote Periplus, and then in Avienus’ Ora maritima. Mastia is also mentioned in a treaty between Carthage and Rome in 348, marking the boundary between them in Iberia. Its mineral wealth, fisheries, agriculture, and harbour, one of the best in the western Mediterranean, made the Punics re-found it in 228 BCE as Qart Hadasht (“New City”), honouring it with a name identical to the metropolis. The Romans renamed it as Carthago Nova in order to distinguish it from the mother city. The importance the Punics attached to their “New City”, so as to serve as their local capital and springboard for the conquest of Iberia, shows that Gadir could not serve this purpose, among other things, due to antagonisms with the Gaditan Phoenicians, which would explode – even before the Punic Wars – in open hostilities.

Greeks and natives “became united in a single state,

consisting of barbarian and Hellenic laws.” (Strabo)

Entering the Punic sphere, we come to realize the way the Phoenician colonial network was created: through infiltration of already existing settlements that soon passed under their full control – without excluding the use of violence in case the locals resisted. By contrast, the Hellenes, especially the Ionians, such as the Phocaeans and the Massaliotes, contrary to the tactics of the Dorians, had a quite different approach. Referring to the foundation of Emporion, Strabo wrote:

“The Emporians lived before on an islet off the coast that now is called Palaiápolis [old city]; for they now live on the mainland. Emporion is a double city (a dipolis), divided by a wall, having before, as neighbours, some [indigenous] Indigetes… Because they became united after some time in a single state, consisting of barbarian and Hellenic laws, as it also happened in many other cities.”

Therefore, there were three phases of colonization: a) a separate settlement; b) peaceful coexistence after a spirit of mutual trust had been established through cooperation; and c) a commonwealth.

The Contestani’s neighbours to the southwest were the Bastetani or Bastuli, and their towns, Baria, Ábdera, Sexi, Malaca, Carteia, Bailo, are mostly mentioned as Phoenician colonies. Baria (present-day Vera, or the fishing village of Villaricos), is said to have financed Hannibal’s campaigns from the local silver mines. There follow Ábdera (today’s Adra), and Sexi (Ex), modern Almuñécar, whose residents sometimes still call themselves sexitanos; a Phoenician settlement was “planted” there in about 800 BCE. As for the seaport town of Ábdera, it was used by the Punics as an emporium. Very few make clear it was a former Grecian colony…

Break: Ábdera, Democritus and Plato

● It is not the first time that places allegedly connected with Phoenicians or Punics are known by Hellenic names. We can see that in the case of Ábdera in either Thrace or Andalusia. According to myth, both cities were founded by Heracles in memory of his companion, Ábderus, who was devoured by either Diomedes’ mares or Geryon’s cattle, during the 8th or 10th Heraclean labour respectively. Historically, Ἄβδηρα, a city-state on the coast of Thrace, 17 km northeast of the mouth of the Nestos River and almost opposite Thasos, in today’s prefecture of Xanthe (where I was born), was a colony of Clazomenae, founded in 654 BCE. Its prosperity, however, dates from 544 BCE, when most residents of Teos (including the poet Anacreon) migrated to Ábdera to escape the Persian yoke. Clazomenae and Teos were Ionian cities of Asia Minor in the Smyrna area. Ábdera became a wealthy city, the second richest among the allies of Athens, as it was a prime port for trade with the interior of Thrace. As a valuable prize, it was sacked repeatedly by Thracians, Macedonians (from several areas, such as Macedonia, Thrace, Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt) and Romans. The result was a decline in the second half of the 4th century BCE – which was attributed to other reasons, as well: the air of Ábdera, claimed Cicero, was proverbial in Athens as causing stupidity. Yet, it was the place of birth of several philosophers, such as Democritus, Protagoras, Anaxarchus, or Hecataeus of Ábdera, who was also a historian. In addition, Anacreon lived there for some time, but showed no signs of idiocy…

Democritus on an old Greek coin of 10 drachmas

● Democritus (Δημόκριτος, “chosen of the people”, c. 460 – c. 370 or c. 357 BCE), the “father of modern science”, was ignored in Athens. Plato, though he never mentioned him (but, on the contrary, he devoted a dialogue on Protagoras), disliked Democritus so much that he asked from his pupils to burn all his books!(4) They proved to be very effective: we now know just citations of his works, since all of them disappeared in the Dark Middle Ages. Democritus and his master, Leucippus, from Miletus, or from Ábdera, were those that formulated an atomic theory of the universe – the idea that everything is composed of various imperishable, indivisible elements called atoms. Democritus travelled a lot spending the money his rich father left him. He praised the Egyptian mathematicians and became acquainted with the Chaldean magi. He was cheerful and always ready to see the comical side of life – but was intentionally misunderstood: they claimed that he laughed at the foolishness of men. That’s why they described him as the laughing philosopher, with Abderitan (incessant) laughter, and also an Abderite, meaning a scoffer, or mocker. The Athenian stupidity about the Abderitan air must have jumped from Plato’s mouth into Cicero’s writings because of Democritus…

Democritus was ignored in Athens. Plato, though he never mentioned him, disliked him so much that he asked from his pupils to burn all his books!

- (4) No wonder that Plato, who rejected the Athenian democracy as prone to anarchy, is included in a list of major advocates of anti-democratic thought (see Chronicle 4. On Democracy), together with: Friedrich Nietzsche (German philosopher, who discarded the so-called “democracy” of his time as “Christianity’s heir”); Charles Maurras (French writer, monarchist and fascist, who asked for the assassination of his opponents); Hubert Lagardelle (French syndicalist, a Proudhonist who later degenerated into a fascist); Robert Michels (German-Italian sociologist, who passed from socialism and revolutionary syndicalism also to fascism); Oswald Spengler (German historian, a “critical” supporter of Hitler, although he considered him vulgar); Martin Heidegger and Carl Schmitt (German Nazi philosophers); Elazar Shach (Israeli fundamentalist rabbi, a champion of Judaic law and an enemy of democracy). Within this framework, with this “company” (except, of course, Nietzsche), what is the real meaning and worth of the Platonic Republic?

● See the next two additional Chronicles 23-24, on the incessant struggle between the defenders and the opponents of Freedom of Thought and Speech.

The scientist philosopher was a determinist and materialist, believing everything to be the result of natural laws. Unlike Aristotle or Plato, he tried to explain the world without reasoning to a purpose, or final cause. The idealists became so pre-occupied for centuries with the teleological question that hindered progress. Democritus, with Leucippus and Epicurus, proposed the earliest views on the shapes and connectivity of atoms. Therefore, their theories appear to be more aligned with those of modern science than any other theories of antiquity. Yet, the so-called “exile of atomism”, after its rejection by authorities such as Aristotle, Plato, and the Christian Church, as well, lasted too long, until the 17th century, when it was resurrected by Gassendi and Descartes. In the meantime, all writings by Leucippus and Democritus, and most of Epicurus, were “lost”. The loss is irreplaceable if we take into account the vast scope of the Democritean work regarding ethics, natural science, mathematics, cosmology, music, art and literature, etc. Suffice it to say that among the works of this traveller-scientist-philosopher, there was one entitled Ocean Periplus… Other titles we’ll never read: Pythagoras, The Horn of Amalthea, On the Planets, On Nature, On the Mind, On Rhythms and Harmony, On Homer, On Poetry, On Song, On History, On Painting, On the Sacred Writings of Babylon, Planispheres, Chaldaean Account, Phrygian Account…

Democritus on an old Hellenic banknote of 100 drachmas

● Book burning, suggested by Plato, was included among the favourite “sports” of the Christian Church. But it wasn’t the only one. Another method of censorship was copying classical works in the medieval monasteries. Behold the grim, dismal picture Catherine Nixey has painted in her thorough research, The Darkening Age / The Christian Destruction of the Classical World (see also our next two Chronicles):(5)

- (5) Catherine Nixey – how ironic! – is the daughter of a nun and a monk. However, her parents were anything but dogmatic (a rare exception); thus she was not indoctrinated (brainwashed).

Medieval scribe copying manuscripts

(19th-century illustration)

“In the silent copying-houses of the monks… gestures were used to request certain books: pagan books were requested by making a gagging gesture.(6) Unsurprisingly, the works of despised authors suffered. At a time in which parchment was scarce, many ancient writers were simply erased, scrubbed away so that their pages could be reused for more elevated themes. Palimpsests – manuscripts in which a text has been scraped (psao [ψάω]) again (palin [πάλιν]) – provide glimpses of the moments at which these ancient works vanished… The work of Democritus, one of the greatest Greek philosophers and the father of atomic theory, was entirely lost.”

- (6) “Books approved by the Church would be stamped or marked by the word ‘Imprimatur’ – ‘Let it be printed’.” (C. Nixey). Centuries later, Mayakovsky would suffer due to similar stamps or marks.

“This theory – an Epicurean one [in Roman times] – offered an alternative view to the idea of a ‘Creation myth’, and stated that everything in the world was made not by any divine being but by the collision and combination of atoms… These particles were invisible to the naked eye but had their own structure and could not be cut (temno [τέμνω > ἄ-τομον, a-tom]) into any smaller particles… Everything that you see or feel, these materialists argued, is made up of two things: atoms and space… The distinct species of animals were explained by a form of proto-Darwinism… ‘No thing is ever by divine power produced from nothing’, wrote Lucretius in his great poem, On the Nature of Things, and ‘no single thing returns to nothing’. Atomic theory thus neatly did away with the need for and possibility of Creation,(7) Resurrection, the Last Judgement, Hell, Heaven and the Creator God himself.

- (7) “Creation happened, as a Christian theologian infamously stated, on 23 October, 4004 BC”. (C.N.)

Book burning: the favourite “sport”

of the Christian Church…

“In the ensuing centuries, texts that contained such dangerous ideas paid a heavy price for their ‘heresy’… Some of the greatest figures in the early Church rounded on the atomists. Augustine disliked atomism for precisely the same reason the atomists liked it: it weakened mankind’s terror of divine punishment and Hell.

“Democritus had perhaps done more than anyone to popularize this theory – though not only this one. Democritus was an astonishing polymath who had written works on a breathless array of other topics. A far from complete list of his titles includes: On History; On Nature; The Science of Medicine; On the Tangents of the Circle and the Sphere; On Irrational Lines and Solids; On the Causes of Celestial Phenomena; On the Causes of Atmospheric Phenomena; on Reflected Images… The list goes on. Today Democritus’s most famous theory is his atomism. What did the other theories state? We have no idea: every single one of his works was lost in the ensuing centuries. As the eminent physicist Carlo Rovelli wrote, after citing an even longer list of the philosopher’s titles: ‘the loss of the works of Democritus in their entirety is the greatest intellectual tragedy to ensue from the collapse of the old classical civilisation’. (See the Appendix on Democritus at the end of this Chronicle).

“Democritus’s atomic theory did, however, come down to us – but on a very slender thread: it was contained in one single volume of Lucretius’s great poem, that was held in one single German library, that one single intrepid book hunter would eventually find and save from extinction. That single volume would have an astonishing afterlife: it became a literary sensation; returned atomism to European thought; created what… was called ‘an explosion of interest in pagan antiquity’, and influenced Newton, Galileo and later Einstein.”

Proto-Aeolic or Proto-Ionic capital with oriental influences from the Santuary of Baal Hamón in Gadir (7th century BCE)

SAILING PAST MAENACA AND MALACA, after this highly instructive break, we finally drop anchor at the Bay of Gibraltar. Carteia was built at its most northerly point, about halfway between the modern cities of Algeciras and Gibraltar, on elevated ground, at the confluence of two rivers, overlooking the sea. According to Strabo, it was founded circa 940 BCE, as the emporium of K’rt, meaning “City” in Phoenician (compare Qart Hadasht, i.e. Carthage, “New City”). The area had much to offer a merchant; the hinterland behind Carteia was rich in wood, agricultural products, lead, iron, copper, and silver. Dyes were another much sought-after commodity, especially those from the murex shellfish, used to make the prized “Tyrian” purple.(8) Due to its strategic location, the city played a significant role in the Punic Wars. In the Battle of Carteia in 206, the Punic fleet was defeated by the Romans, who captured the colony circa 190 BCE.

- (8) The “Tyrian” purple was, in fact, Minoan: see Chronicle 19, footnote 6.

The Bay of Gibraltar: Algeciras (W), Calpe (E)

and Carteia (in the middle?)

Passing through the Strait and into the Atlantic, we are surprised to hear that Bailo was none other than Gadir. The information, however, cannot be verified, and the closest to the name “Bailo” we can find is Baelo, near the present-day village of Bolonia, around Tarifa, at the southernmost point of Europe – but rather far from Gadir. The town served as a trade link with northern Africa (Strabo: “hence the crossings to Tingis of Maurusia”);(9) nevertheless, it was abandoned because of earthquakes. Eventually, we realize we’re sailing in an area colonized by Heracles – or, in other words, by the Mycenaeans: not only Ábdera (or Ábderos), but also Carteia (Carpeia, Carpaea or Carthaea), and Bailo-Baelo or Belōn, appear to have links to the great hero. Carteia, wrote Strabo citing Timosthenes of Rhodes, was previously called Heraclea, after its founder. Some identify it with Algeciras, Paco de Lucía’s hometown, on the west side of the bay, others say on the contrary it was located on the east side, on Calpe, i.e. the Rock of Gibraltar; there are those also who connect it to Tartessos claiming that once the latter disappeared, many confused it with Carteia (e.g. Pausanias: “Tartessos, some people say, used to be the old name of Carpeia”). Other settlements of the Heraclean colonizing labour were Mellaria (Menlaria, or Melouria, modern Tarifa), and also Gadir; sometimes even Tartessos is included in the list. Some, very few, on the other hand, identify the legendary city with modern Sanlúcar de Barrameda. Wishful thinking, most probably, on either side…

Gulf of Gadir and the three islets with Greek names:

Erytheia, Kotinoussa, Antípolis

As for the Pillars of Heracles, the northern one on European soil is called Calpe, or Alybē (Gibraltar), “small in size but rising sharply to a great height and looking like an island from afar” (Strabo), while the southern one, Abylē or Abyla (Ceuta), is rather low. Their peculiarity is that their sovereignty is exercised nowadays by foreign powers: Gibraltar, on Spanish territory, is controlled by Britain; Ceuta, on Moroccan soil, by Spain. The Phoenician Abyla, founded in the 7th century BCE, passed under the control of the Phocaeans who renamed it as Heptá Adelphoí (Seven Brothers). The Romans, as usual, transcribed the Grecian toponym into Latin as Septem Fratres, or simply Septem (hence perhaps its current name), and used Ceuta almost exclusively as a military post. The strategic importance of the Strait was obvious to everyone.

There is another settlement, beyond the Pillars and on African soil, presented as a Punic colony of the early 5th century, possibly with prior Phoenician presence, called Tingis (today’s Tangier). Taking advantage of Carthage’s crushing defeat in Sicily in 480 BCE, the Phocaeans should have taken control of this town, too, dominating – at least for a while – in that area of strategic importance, during the Punics’ isolationist period after their defeat. Like so many other towns, Tingis in fact was neither Phoenician, nor Greek, but, in this case, Berber. According to a Graeco-Roman mythological tradition, cited by Plutarch, Tingis was the wife of the giant Antaeus, king of Libya (Maghreb) and son of Poseidon and Gaea, who was killed by Heracles. In Berber mythology, the founder of the city was Syfax, son of Tingis and Heracles. The tomb of Antaeus, with his giant skeleton, was found in Tangier by the Roman rebel Quintus Sertorius in the 1st century BCE, while the “cave of Heracles”, where the hero supposedly slept before he stole the apples of the Hesperides, is located 14 kilometers from the city to the west.

The Strait of Gibraltar with the Pillars of Heracles

The colonizing activity apparently continued after the Trojan War, since we are told that, despite the reports to the contrary, there were Hellenic (later Roman) settlements beyond the Pillars of Heracles. One of them was located between Gadir and the city of Tartessos, at the mouth of the Río Guadalete: it was Portus Menesthei (Μενεσθέως Λιμήν), probably the present-day El Puerto de Santa María, locally known simply as El Puerto.(10) Even the Gaditan Phoenicians, wrote Strabo, offered sacrifices in Menestheus’ oracle. As one of Helen’s suitors, he fought in the Trojan War. But afterwards, according to some writers, he was expelled from Athens by the descendants of Theseus, and found refuge with his entourage in Iberia. (See Chronicle 26, Odysseys in the Aftermath of the Trojan War: Colonization of Iberia). Lastly, there was another Hellenic settlement located next to Huelva to the West: it was Calathussa, today’s Aljaraque.

- (10) The word “Port” is preserved in the toponym throughout its history: the Arabs (Moors) invaded Iberia in 711 CE and renamed the port to Alcante or Alcanatif, meaning Port of Salt, due to the production of salt since the time of the Phoenicians. Finally in 1260, the Castilians, who occupied the city, renamed it to Santa María del Puerto.

The Lioness of Baena (Córdoba) with Greek

and oriental influences (6th century BCE)

Portus Menesthei, in “historical terms”, might not be that old, since the Hellenes of the Homeric era (at least their goods) arrived at Iberian ports later, in the 9th – 8th centuries BCE. Those who transported the Greek ware and other products might very well have been the Phoenicians, due to their artistic quality, which the Canaanites were unable to achieve. Such an excellent ceramic, an Attic cylix, a wine-drinking vessel, was found in Medellin of Badajoz, in Extremadura. The presence of such a beautiful cup so far from the coastline is explained by the so-called Silver Route that probably crossed western Iberia from north to south to facilitate transport of mineral wealth from Galicia to Tartessian harbours.

Hellenic culture, art, ideas, habits, etc. could not be transported on

Phoenician ships, making the Greek presence in Iberia necessary…

What the Phoenician ships could not transport and, therefore, made the Greek presence absolutely necessary in Iberia, was Hellenic culture, art, ideas, models, architecture, burial habits, etc. Taking into account that perhaps the Minoans were not Greeks, it seems that Iberia was found under Hellenic influence for the first time during the Mycenaean period. But this is half-true and, therefore, half a lie (at least), given that the Mycenaeans were civilized thanks to the Minoans. Consequently, Minoan and Mycenaean influences on Iberian cultures were very similar, if not identical. At that time, there was perhaps no Tartessos. Minoans and Mycenaeans inseminated the local cultures they found in Iberia, and the Tartessian civilization germinated some time later, when there were no Greeks around anymore. It took them at least half a millennium to wake up from their lethargic “Dark Ages” and re-appear in the peninsula. In the meantime, the rich rewards were reaped by the Phoenicians and Punics…

Major Hellenic colonies in Iberia before the Punic conquests (c. 300 BCE): Rhode, Emporion, Callípolis, Sálauris, Zácantha, Hēmeroscopeion-Artemisium, Acra Leucá, Alonís, Helice, Ábdera, Maenaca, Portus Menesthei, Calathussa: they are all located in Spain. So, the Iberian periplus

I’ve tried to revive in this Chronicle ended up as just a circumnavigation of Spain.

Appendix on Democritus

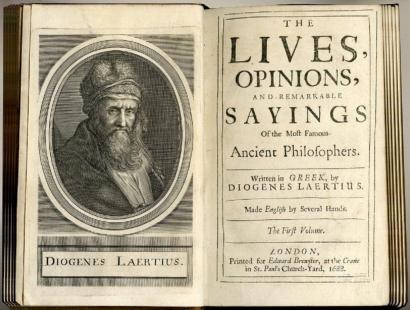

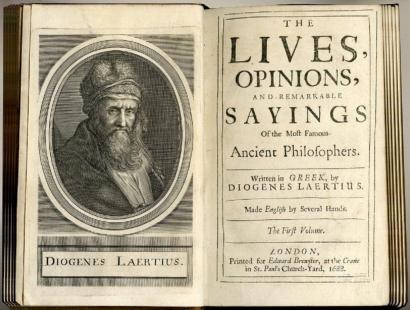

“Aristoxenus, in his Historical Notes, affirms that Plato wished to burn all the writings of Democritus that he could collect, but Amyclas and Cleinias, the Pythagoreans, prevented him, as it would be of no use, for the books were already widely circulated… Plato, though he mentions almost all the early philosophers, never once alludes to Democritus, not even where it would be necessary to controvert him, obviously because he knew he would have to match himself against the greatest of philosophers”… (Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, by Diogenes Laërtius)

Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laërtius

Avoiding the encounter, Plato passed the torch to Aristotle who wrote a monograph on Democritus, praising him for arguing from sound considerations appropriate to natural philosophy, and regarding him as an outstanding rival. This may be the reason why this monograph, albeit Aristotelian, was “lost”; only a few passages quoted in other sources have survived. The predominance of Platonic philosophy in the 4th century BCE, and the spread of Platonic schools must be the reason why Democritean thought and work was brushed aside and vanished. What survived could not pass through the “Symplegades” of Christian “zealots”; and what has been brought down to us includes many fragments, most of which, however, are on ethics and not physics.

Democritus on a Greek stamp

● The world is born when many atoms of various shapes gather and produce a whirl, separating the fine bodies, while bringing together the heavier bodies at the centre in a first sphere (earth). As long as the atoms are infinite, and the void is also infinite, our world is anything but a unique phenomenon. Thus, the atomists are the first thinkers to have clearly put forward the idea that there are infinite worlds. In their system there are three eternally existing elements: the atoms, the void, and motion-change (kinesis). Proposing that motion-change is eternal, Democritus was aware that in this way he removed all anthropomorphic elements from the natural world.

Portrait of a philosopher,

probably Democritus

The mechanisms of nature function without being regulated by any higher power. Can it be that everything in nature happens without order, or by chance? Judging by Plato and Aristotle, many after Democritus have interpreted the atomist theory in this way. Plato launches a harsh attack in his Laws against Democritus (without mentioning his name), and the “wicked, disrespectful” philosophers, who claim that the greatest and finest things came to be with no intervention of some intellect or god, and are works of nature and chance. These philosophers, claims Plato, are wrong in underestimating the role of the soul, to which they attribute a material substance, but also of the “intelligent purposefulness” governing the universe. The controversy with Democritus must be the motive for the late Plato to write Timaeus, in an attempt to construct a teleological cosmology in contrast to the supposedly “mechanistic” Democritean universe. Once more, Plato does not mention his rival directly, not even when he adopts a peculiar system of mathematical atomism, in which the atoms of Democritus are replaced by elementary triangles.

Diogenes details the Democritean opera

On Ethics: Pythagoras | On the Disposition of the Wise Man | On Those in Hades | Tritogeneia (so called because three things, on which all mortal life depends, come from her) | On Manly Excellence or On Virtue | Amalthea’s Horn (the Horn of Plenty) | On Tranquillity | Ethical Commentaries | Well-Being (not to be found) [was already “lost” in the 3rd century CE, the time of Diogenes].

On Nature: The Great Diacosmos (the Major World System; the school of Theophrastus attribute it to Leucippus) | The Lesser Diacosmos (the Minor World System) | Cosmography, Description of the World | On the Planets | On Nature (I) | On the Nature of Man or On Flesh (II) | On the Soul: On Reason | On the Senses | On Flavours | On Colours | On the Different Shapes (of Atoms) | On Changes of Shape | Confirmations (summaries of the aforesaid works) | On Images or On Foreknowledge of the Future | On Logic or Criterion of Thought (I, II, III) | Problems.

Miscellaneous: Causes of Celestial Phenomena | Causes of Phenomena in the Air | Causes on the Earth’s Surface | Causes Concerning Fire and Things in Fire | Causes Concerning Sounds | Causes Concerning Seeds, Plants and Fruits | Causes Concerning Animals (I, II, III) | Miscellaneous Causes | Concerning the Magnet.

On Mathematics: On a Difference in an Angle or On Contact with the Circle or the Sphere | On Geometry | Geometrics | Numbers | On Irrational Lines and Solids (I, II) | Extensions (Projections) | The Great Year or Astronomy, Calendar | Contention of the Water-Clock (and Heaven) | Description of the Heaven | Geography | Description of the Pole | Description of Rays of Light.

On Music: On Rhythms and Harmony | On Poetry | On the Beauty of Verses | On Euphonious and Cacophonous Letters | Concerning Homer or On Correct Epic Diction and Glosses (Tongues) | On Song | On Words | A Vocabulary.

On the Arts: Prognostication | On Diet or Dietetics | Medical Regimen | Causes Concerning Things Seasonable and Unseasonable | On Agriculture or Geometrics, Concerning Land Measurements | On Painting | Treatise on Tactics | On Fighting in Armour.

Supplementary (Some include as separate items in the list the following works taken from his notes): On the Sacred Writings of Babylon | On Those in Meroë | Ocean Periplus, A Voyage Round the Ocean | On History | A Chaldaean Treatise | A Phrygian Treatise | Concerning Fever and Those Whose Malady Makes Them Cough | Legal Causes and Effects | Problems Wrought by Hand.

The other works which some attribute to Democritus are either compilations from his writings or admittedly not genuine, adds Diogenes.

Next Chronicle 23. THE GENOCIDE OF THE HELLENES ● “Burning Books, Burying Scholars” ● Libraries Burned ● Massacre of Thessalonica ● Delphi, the Serapeum and the Temple of Artemis in Ruins ● Sacrilege of Alexander’s Sōma ● The Darkening Age